| Home |

| Projects |

| Publications |

| Robot Videos |

| Publicity |

| Photos |

| PhD Students |

| Applying for an RA? |

| Links |

| Bipedal Home Page| ROBEA Home Page | MABEL| Our Biped Publications | Biped Control Book | Jessy W. Grizzle| |

. .

|

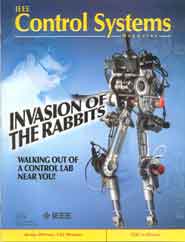

RABBIT |

. .

|

RABBIT and its caretaker

In mid-July 2002 we began tests on an experimental biped called RABBIT located at the Grenoble Images Parole Signal Automatique (GIPSA) in Grenoble, France. The engineer in charge of RABBIT is Gabriel Buche.Experiments on RABBIT (Most current work is listed first)

Copyright: These videos belong to me, my colleagues, and/or my students. You may use them for your own ends as long as you cite their source.- Experiment on running conducted 24 September 2004: RABBIT RUNS!

- Extended walking conducted in September 2004: Extended Walking(26MB) (Format is .mwv so it will only work on a PC.) Note: Robot's safety provided by a cable.

- Extended walking under a perturbation conducted in September 2004: Extended Perurbation(20MB) (Format is .mwv so it will only work on a PC.) Note: The robot's mass is 32 Kg; a 5 Kg mass has been attached to the torso with no change to the control algorithm, which is the same as that used in the above experiment.

- Extensive walking experiments ran in early March, 2003. (Eric's Movie Page). Note: The wheels are to prevent damage if the robot falls. They are actually a perturbation to the system, not a support. If you look closely, you can see that the pipe connecting the wheels to the ground is a prismatic joint. The wheels are not supporting the bar at all, and consequently will not support the robot until the hips fall below a certain point that is not attained in normal walking.

- An earlier walking experiment ran on February 28, 2003. 28Feb2003Walking(7MB). (Format is .mwv so it will only work on a PC.) Note that we currently start the robot by simply pushing on its torso. We have not yet implemented the control code for an automatic start. The controller is quite robust. Note the flexing of the radial support bar as the robot walks. The robot's handler is being careful in these initial experiments. If the robot were to fall, it could break some rather expensive parts. This is normal in initial experimental work.

- You may find it interesting to compare the real experiments to animations of a similar walking motion: Movie_1. and Movie_2..

- Other experimental work is available at ROBEA Video Page [The French part of this site is sometimes more up to date; it is worth checking out: ROBEA Video Page (French portion of web site)]

- Another source of animations and data [Supplemental Material for Paper to Control Systems Magazine].

- Still other sources of animations and data [Supplemental Material for Paper to CDC 2003].

- Other animations of RABBIT.

About our controller designs

Our feedback controller designs are VERY DIFFERENT from the traditionally used method of trajectory tracking. We never compute a planned trajectory. To see the difference, consider this: could you imagine what would happen if you pushed backward on Asimo (Honda's famous robot) while he was walking? He would surely fall down. On our robot, if you push him backward, he begins to walk backward, WITHOUT ANY CHANGE in the feedback controller. This is because we have programmed a posture principle into the robot: the relative angles of the knees and the relative angles between the torso and thighs are controlled as a function of the angle of the center of mass of the robot with respect to the stance foot. Therefore, if the center of mass moves backward, the swing leg moves backward, and if the center of mass moves forward, the swing leg advances forward and prepares for contact with the ground. This is very different than trajectory tracking. Our controller creates an asymptotically stable orbit, similar to that of a van der Pol oscillator, except we have to deal with the additional problems caused by impacts. When you see the van der Pol oscillator converge to a periodic orbit, you do NOT think that this is due to a planned trajectory, you understand that is due to an inherent stabilizing mechanism in the oscillator. Similarly, with our controllers, the robot converges to a periodic trajectory without us forcing it with a periodic trajectory. We can compute feedback controllers that are optimal with respect to almost any cost function, such as minimal energy. We can even take into account friction at the joints in the controller design. For more details, see the papers at Robotics Publications Page, especially: RABBIT: A Testbed for Advanced Control Theory (This paper empahsizes the ideas and down plays the mathematics; the other papers are quite mathematical).Key points of RABBIT

- RABBIT was conceived to advance the scientific understanding of feedback-controlled bipedal locomotion. The robot is purposefully underactuated (no feet) so that the ZMP principle does not even apply. Our analysis deals directly with the issue of underactuation.

- We have gone as fast 1.0 m/s. This was achieved in our third week of experimentation!

- Currently, no other biped has a complete stability proof! Our controllers are analytically derived. We have a beautiful stability analysis for the closed-loop behavior of the robot under our controller designs.

- Analysis reduces tweaking. The first controller we implemented resulted in walking on the very first try!

- We can vary the walking speed at will! We use a combination of switching controllers and integral control. Our analysis integrates control action within stride and stride-to-stride.

- Our control designs are quite robust. The basins of attraction of our designed walking motions are so large that a simple push on the robot's torso is sufficient for entry.

- Our control designs are most sensitive to the amount of energy lost at impact, which is highly dependent on the walking surface. This affects the robot's walking speed, but has only a small effect on stability. To understand why, see our paper RABBIT: A Testbed for Advanced Control Theory available at Robotics Publications.

Eric, Carlos and RABBIT made the evening news in Grenoble, France

Eric Westervelt and Carlos Canudas-de-Wit were interviewed by French Channel 3 at the end of a set of experiments on RABBIT.- Lower quality (smaller, faster to download) version: French Channel 3, 6:55 p.m., March 14, 2003. (The format is .mwv so it will only work on a PC; also, you need the most up to date player for this!)

- Go here for a higher quality, version in MPEG1 (18MB). [This link sends you to the site of my French colleagues. Suggestion: once there, download before playing (right click with your mouse and then use "save target as")].

- Version with English subtitles: French Channel 3, 6:55 p.m., March 14, 2003 (subtitled). (The format is .mwv so it will only work on a PC; also, you need the most up to date player for this!)

Some Animations

- Stable walking up a slope. (The format is .avi ) This uses the same theory as walking on flat ground. See our hybrid zero dynamics papers for RABBIT.

- Stable walking showing center of mass. (The format is .avi )

Back to Robotics Publications Page

Back to Grizzle's home page

Back to ROBEA's home page